NASA’s Scientific Ballooning Handbook references Julian Nott in its dedication. “Julian Nott’s vision, expertise, and leadership helped define the modern era of scientific ballooning. He brought unique talents and perspectives to the field with his innovative designs and engineering excellence and pushed the boundaries of altitude and endurance for manned flight. Nott exemplified the spirit of dedication, curiosity, and technical excellence that elevated ballooning from its experimental roots to a mature scientific platform capable of addressing some of the most profound questions in astrophysics, atmospheric science, and engineering.” December 24, 2025

FAI Ballooning Commission Announces

2026 Hall of Fame Inductee Julian Nott

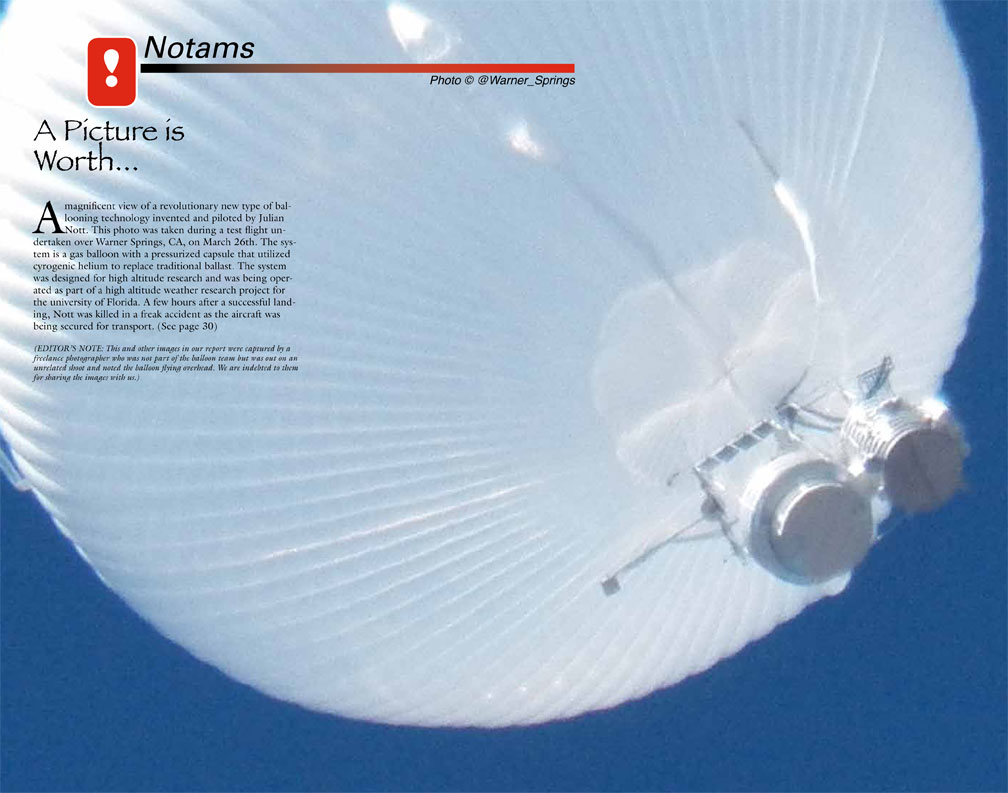

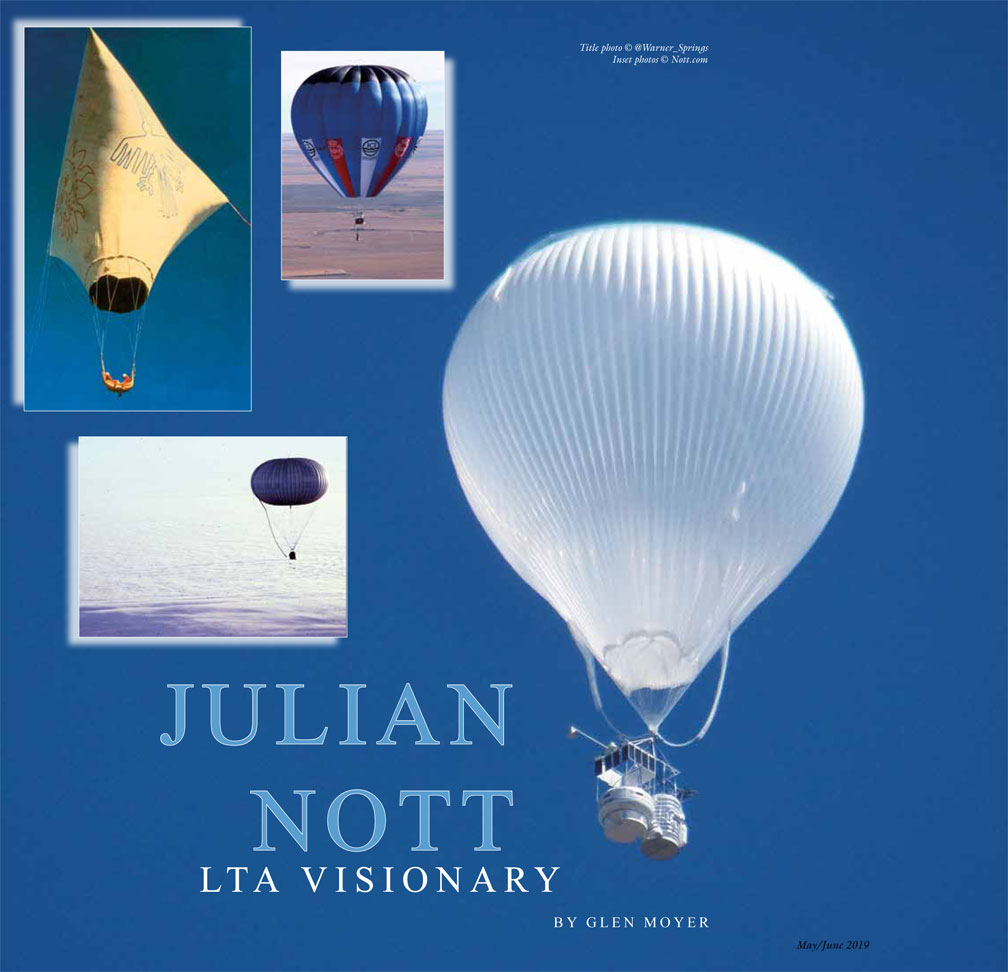

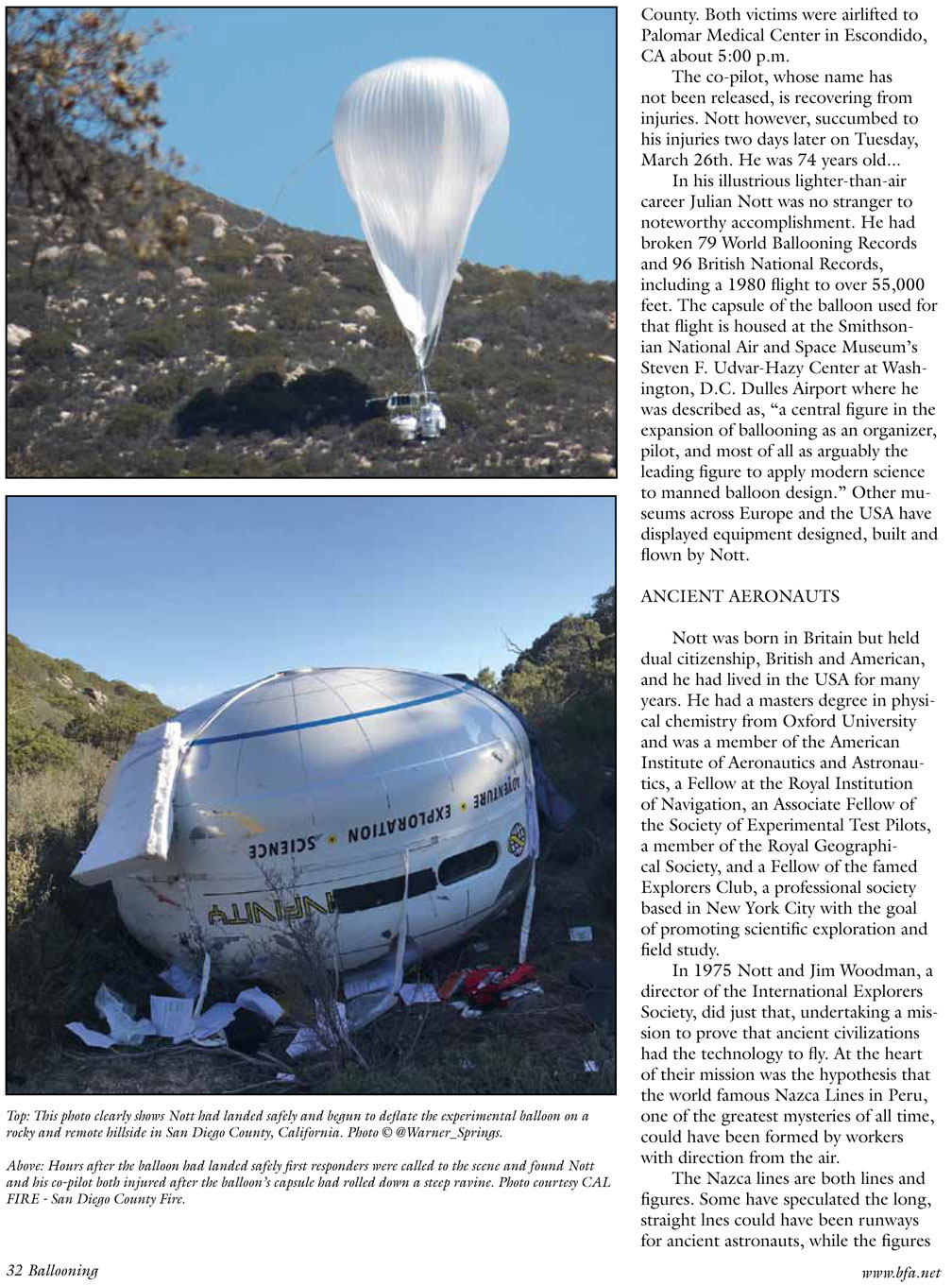

Julian Nott passed away peacefully on March 26, 2019 after suffering multiple injuries from an extraordinary and unforeseeable accident following a successful balloon flight and landing in Warner Springs, California. Julian was flying an experimental balloon that he invented, designed to test high altitude technology.

His loving partner of 30 years, artist Anne Luther, was at his side.

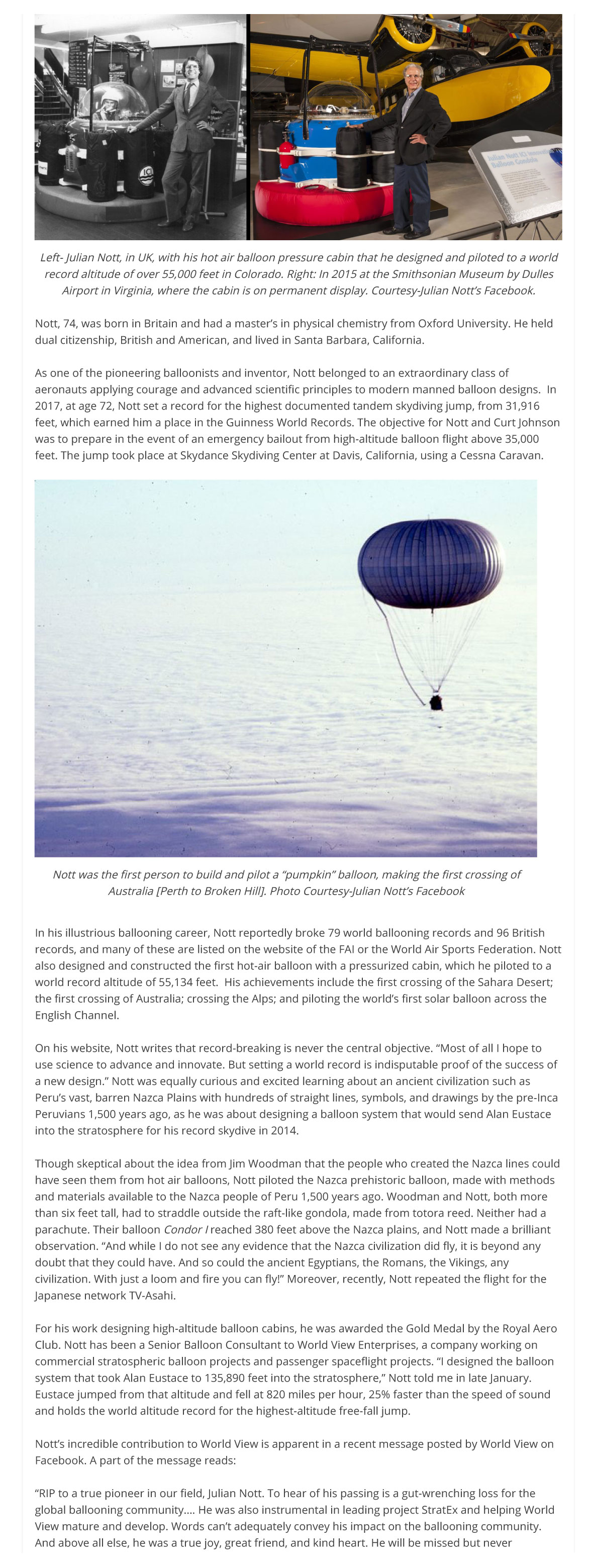

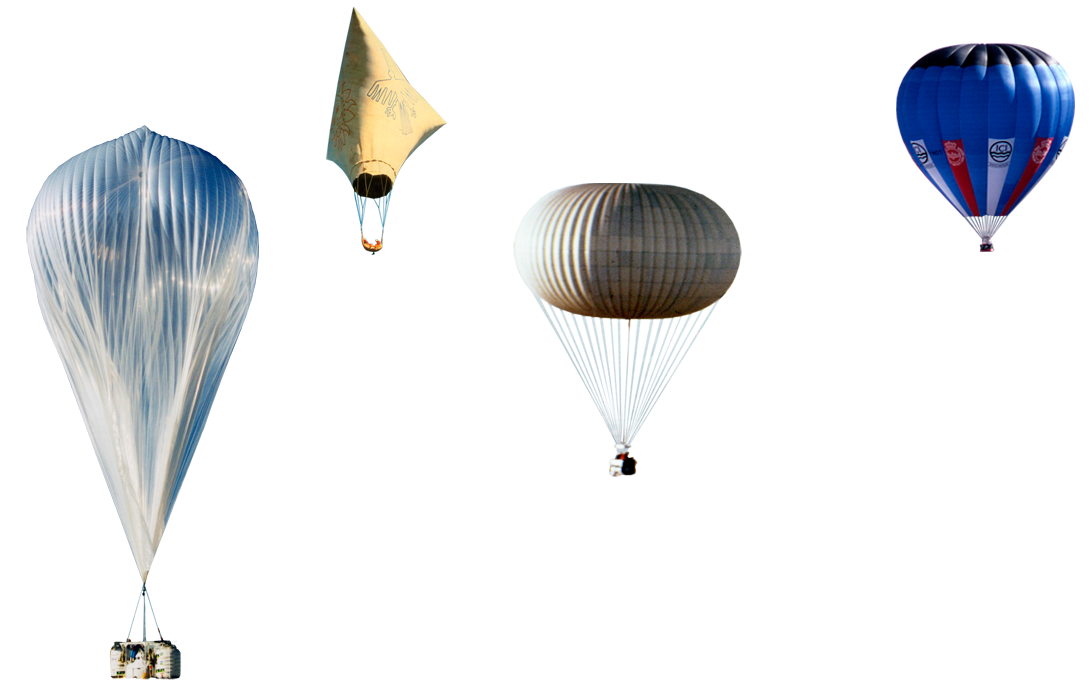

Known as the founder of the modern ballooning movement, and one of its most creative and innovative exponents, Julian was changing the course of balloon history with the development of an entirely new system in which conventional ballast is replaced with cryogenic helium. He has broken 79 World Ballooning Records and 96 British Records including exceeding 55,000 feet in a hot air balloon.

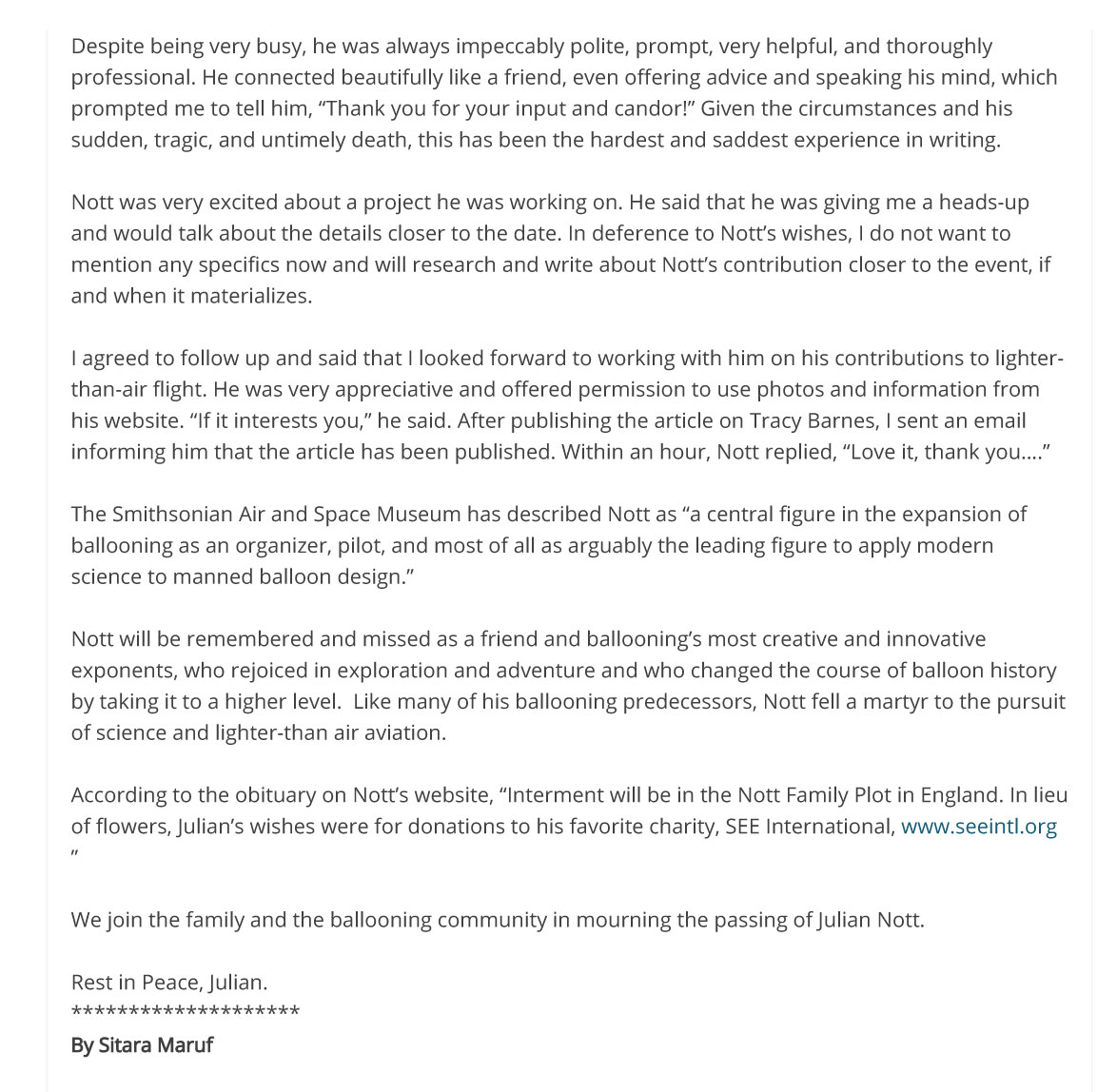

The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum has described Julian as “a central figure in the expansion of ballooning as an organizer, pilot, and most of all as arguably the leading figure to apply modern science to manned balloon design.”

We join the family and the ballooning community in mourning the passing of Julian Nott, an exceptionally brilliant man who rejoiced in exploration and adventure. He will be missed but never forgotten.

His beloved Anne Luther, his brother Robin Nott, and nieces Elizabeth Salmon and Katherine Nott survive Julian. He is buried at the Nott Family Plot in the historic Watts Chapel and Cemetery in Surrey, England.

If you wish to honor the memory of Julian Nott you may make a donation to the Julian Nott Scholarship Fund. Beginning in 2020 a scholarship award will be made to one Santa Barbara High School student, accepted to college and majoring in either science or engineering.

Please make out a check for any amount to The Scholarship Foundation of Santa Barbara and mail it to them at P.O. Box 3620 Santa Barbara, CA 93130 Or you can make a donation on-line here. Please mention the donation is in honor of Julian Nott.

Julian Nott’s archives may be found at the following institutions:

- Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Udvar-Hazy Center, Washington DC

- The International Balloon Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- The Royal Air Force Museum, London, England

- The Flight Test Museum, Edwards Air Force Base, California

- The Aerospace & Civil Engineering Museum, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California

- The National Balloon Museum

- The Society of Experimental Test Pilots Library

- The Brittish Balloon Museum

Contact: Roberta Greene, Roberta.greene@icloud.com

Julian Nott: 1944 – 2019

In Memoriam

By Erin Graffy

The Santa Barbara Independent

How do you hold back a shooting star — that meteor that moves so fast in Earth’s atmosphere that it heats up and glows as it moves through our space?

That was Julian Nott, the effervescent balloon pilot and scientist, inventor, adventurer, lecturer, and writer, who was grounded in March … but only after a tragic earthbound accident.

Julian was in the process of changing the course of balloon history with the development of an entirely new system in which conventional ballast is replaced with cryogenic helium. Julian was flying the experimental balloon he designed to test high-altitude technology. Several hours after landing safely from a trial run in San Diego County, Julian returned into the balloon’s capsule to extract equipment. The capsule became loose and rolled 400 feet down the mountainside. He sustained a serious head injury and passed away peacefully two days later, with his beloved partner, Anne Luther, by his side.

During his long and extraordinary career, this British maverick had broken 79 World Ballooning Records, and 96 British Records. He is the first balloonist ever to receive the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club, presented for outstanding achievement in aviation (previously awarded to only 34 luminaries, including the Wright brothers and Neil Armstrong). Julian was awarded the prestigious Montgolfier diploma and was the only balloonist ever elected to the elite Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

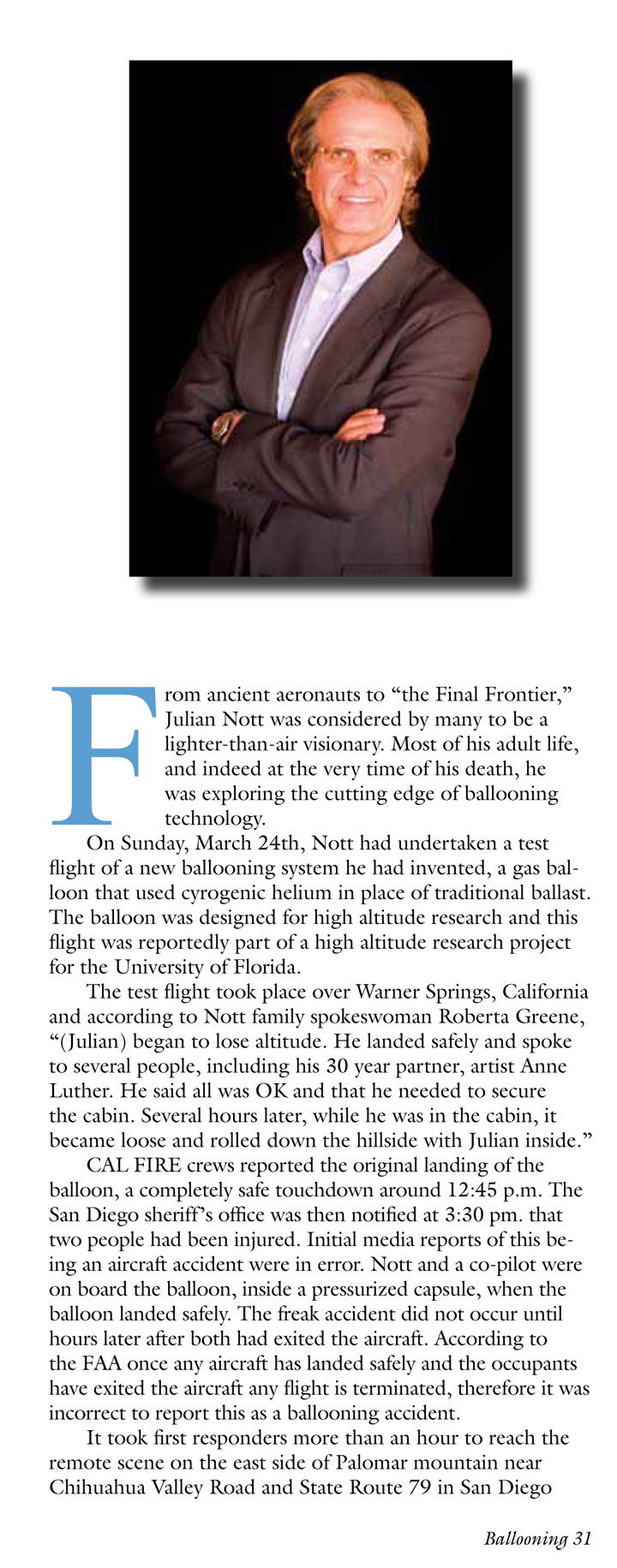

His personality was as buoyant as his equipment. His upbeat demeanor filled every gathering and conversation with lightness and energy. Julian did not suffer fools lightly, and he had that distinct British talent of articulation, with humor and a Monty Python-esque voice of exasperation. He loved a good rousing discourse on politics, and puns and parodies would elicit his jubilant, “Oh HO!” coupled with a conspiratorial laugh.

However, his bon vivant personality completely belied his brilliant, mind-boggling, thinking-outside-the-box genius. He did not just design balloons; he designed the capsule, the launching system, every aspect of how it would move and land. Julian was working on developing balloons for destinations throughout our solar system, and he was particularly enamored with Saturn’s moon Titan. He developed and flew a working prototype Titan balloon at minus 175 degrees Celsius, approximately the temperature of Titan’s atmosphere.

The theme that infused his work — and his lectures — was the concept he called “intellectual courage.” It was born from his study of the history of flight and through his own achievements. It is the courage to dare to dream of something outside our natural experience — outside the box — and then to pursue it passionately with all of our intellectual faculty, taking advantage of accumulated knowledge, calculating the risks, analyzing the data, and then boldly going where no man has gone before.

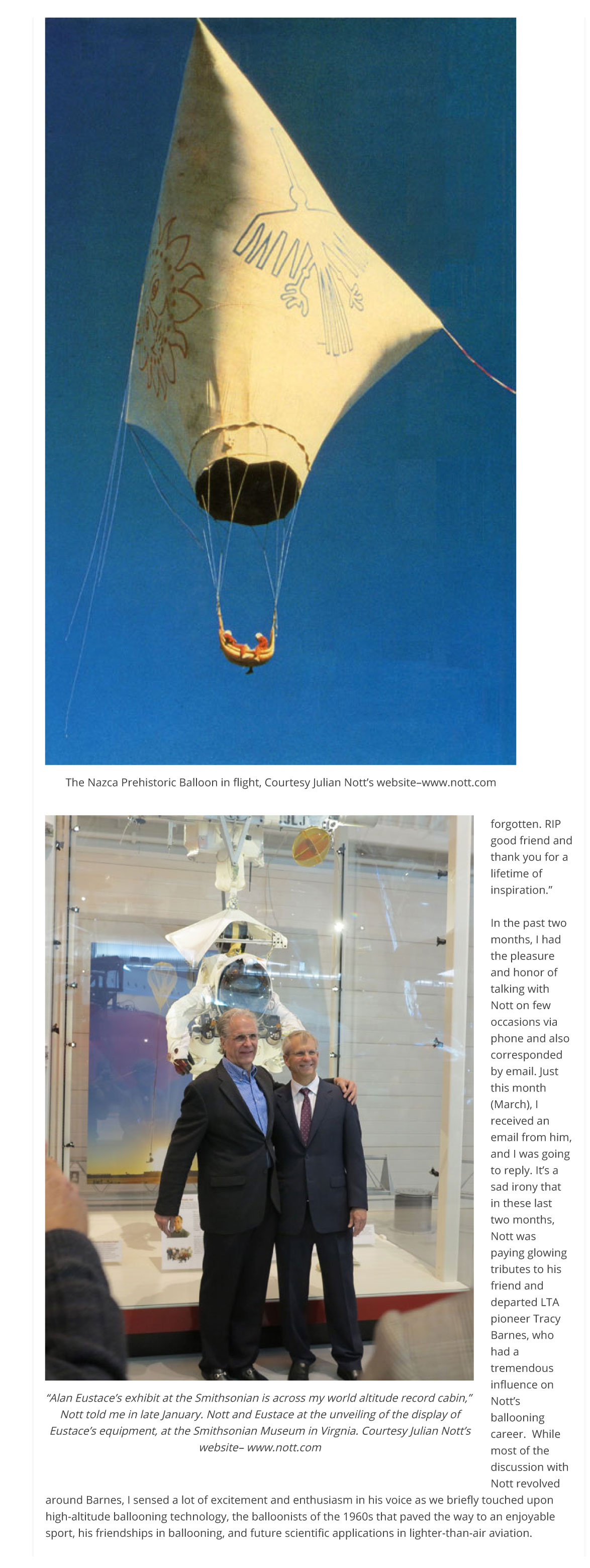

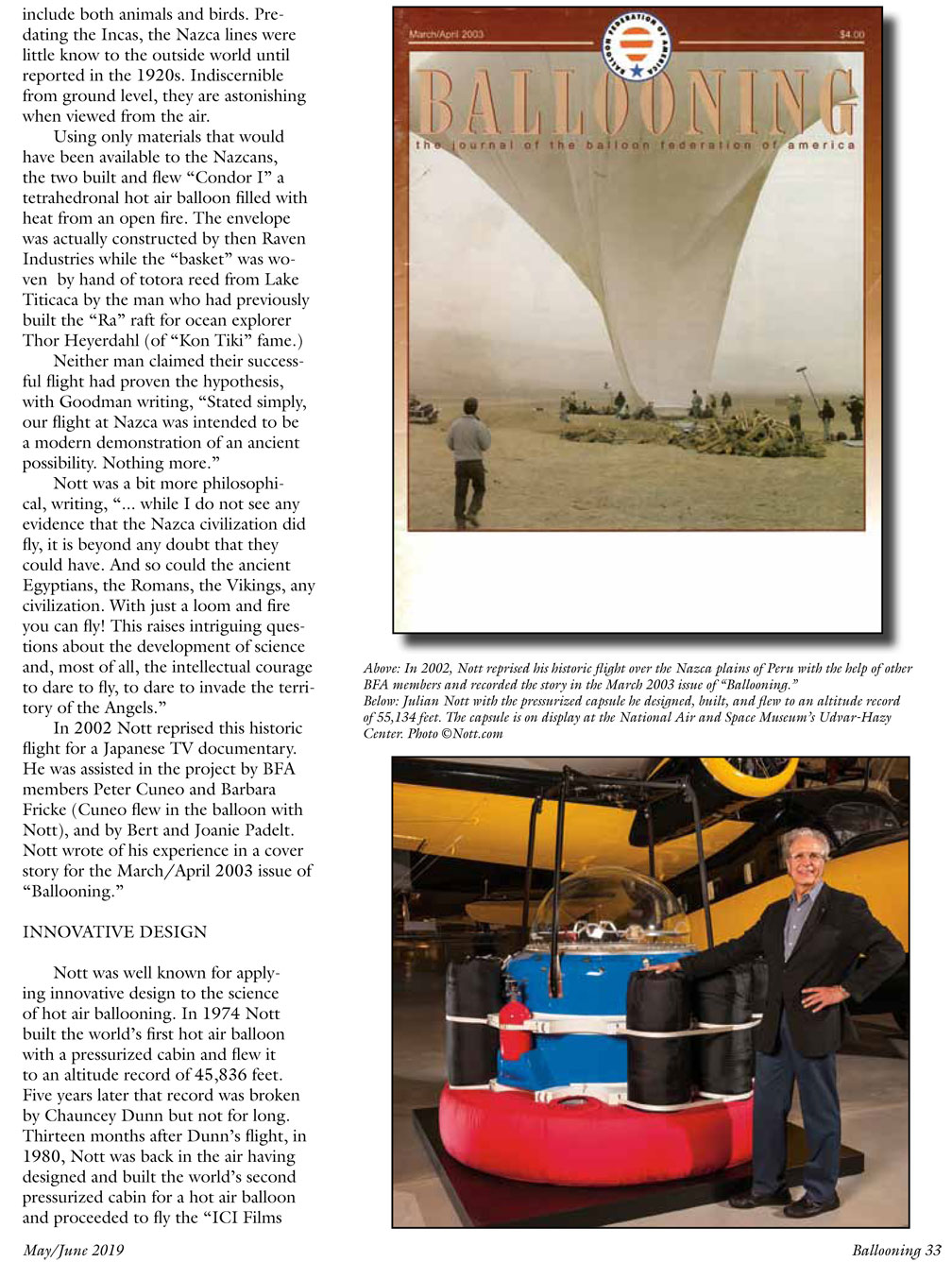

For instance, Julian postulated that the enormous geoglyphs (large designs on the ground) etched on Peru’s vast, barren Nazca Plains could have been viewed by men in balloons centuries ago. He designed and built a balloon made of natural materials available to Peruvians 1,500 years ago, and then piloted it in an open gondola up 350 feet — just to prove it could have been done.

To prove the potential for hybrid energy — using both solar and conventional heat sources — he designed and piloted the world’s first solar balloon across the English Channel.

His fearless determination to venture into terra incognito was never reckless derring-do. Julian was quick to point out that “everything in life is a risk. Even driving a car can carry an element of risk.” But, as Julian amply demonstrated, diligence and dedication could reduce your margin of error; he would engage only in carefully calculated maneuvers. He had never injured himself in ballooning; his last words to Anne after his successful landing, but before his accident, were “I don’t even have a scratch on me!”

His meticulous design engineering showed how it could be done — and then he went ahead to demonstrate it himself. Julian set a world record for the highest documented tandem skydiving jump — from 31,916 feet. And he was 72 years old when he jumped.

However, breaking aeronautical records was not his main objective. “I hope to use science to advance and innovate,” he once wrote, “but setting a world record is indisputable proof of the success of a new design.”

His vision for attempting anything in the universe was infectious. I remember his lecture given at the Kavli Institute of Theoretical Physics at UCSB — a room overflowing with earnest scientists and several Nobel winners, each leaning forward, chin in hand, intently soaking up everything Julian had to postulate.

And yet he could speak to us laymen — a sold-out crowd of Channel City Club members, or the enthralled junior high students at local schools — and not only make us see what could be achieved but also inspire us to think that we could go out and do it ourselves.

The All-American Boy

After graduating Epsom College in Surrey, but before earning his master’s in physical chemistry from Oxford, Julian decided to spend part of his gap year touring America by Greyhound with a friend. Cut from the upper class in Britain, Julian naturally held a less-than-sterling opinion of “the colonies” and took for granted that America was a tad uncouth and bourgeois.

Once here, however, he had a dramatic conversion.

Julian was fascinated with what he heard and observed. And with his keen eye for observation, he definitely keyed into American culture and noted it offered not so much a perfectly classless society but one with class mobility. Through pluck and perseverance, one could move to another place of power, prestige, fame, and fortune. To Julian, America represented endless possibilities: an open society with far less bureaucracy or red tape than Britain. It suited everything in his own personality: independence, energy, enterprise, and achievement.

Brenda Lee’s hit at that time, “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” struck a chord with Julian as the theme of his visit. The Golden Gate Bridge itself was a symbol of man dreaming and reaching out to “close the gap” and using applied technology to achieve this. (Julian actually trademarked his phrase “Math lets dreams take flight.”)

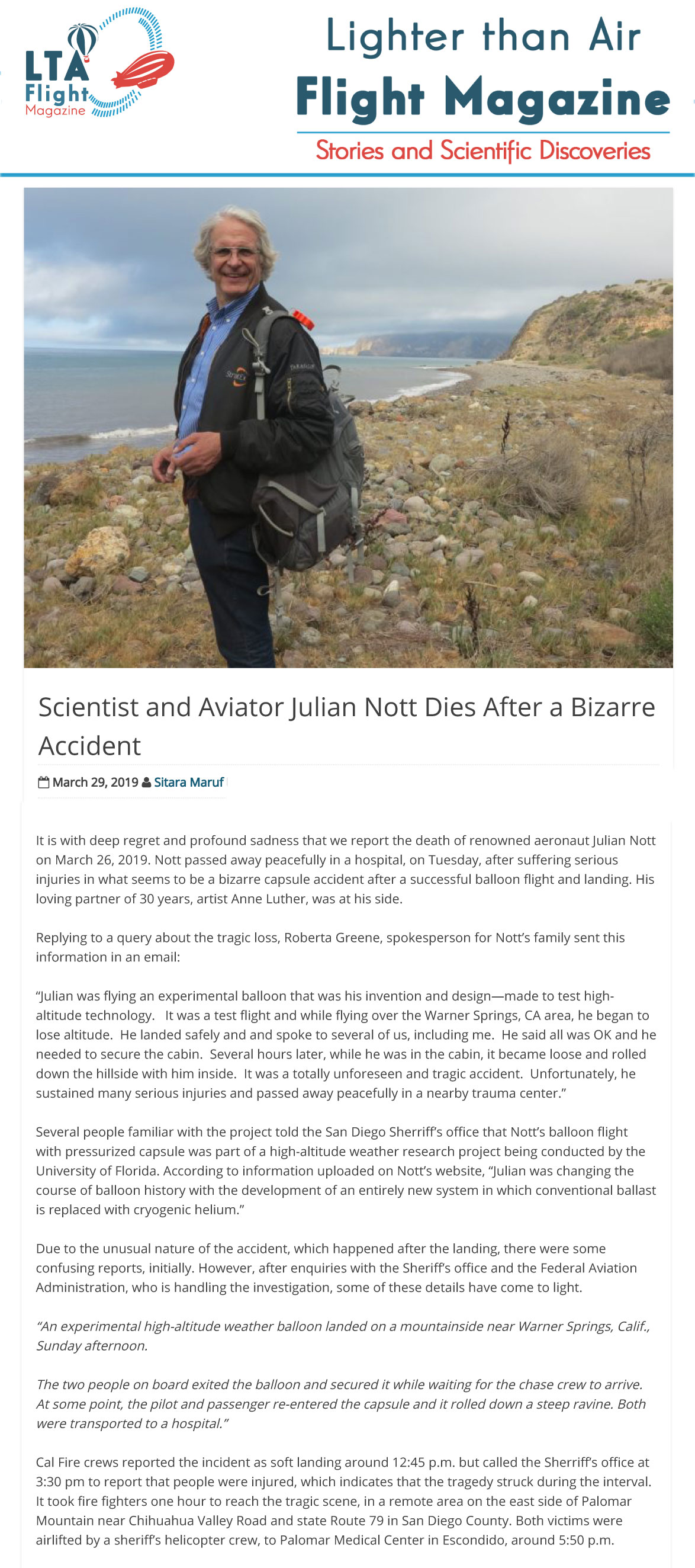

After that trip, Julian was always interested in returning to America and was subsequently thrilled to be proffered the U.S.A.’s O-1A visa, assigned to individuals with an extraordinary ability in the sciences who are internationally recognized. Julian worked with NASA and JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratories); he had been a consultant on the design of the new U.S. Navy Advanced Blimps since 1986. His balloon Innovation —which he designed, built, and piloted solo to a world-record altitude of 55,134 feet in 1980 — was placed on permanent exhibition at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in D.C.

In 2012, Julian became an American citizen and beamed for an entire week. Then he held a citizenship party at which he extolled the country’s virtues, where he pleasantly chided his friends, “Sometimes I think America is wasted on Americans!”

Did I mention his voice? Julian’s sonorous baritone was a thing of beauty, and he happily shared it at parties and at church. It conveyed his unabashed joy and gratitude for the world. People would stop him in public places, commenting on how happy he must be, as he was singing out loud without realizing it.

Perhaps Julian’s favorite all-time quote by Charles Lindbergh could adequately sum up his legacy: “Science, freedom, beauty, adventure: What more could you ask of life?”

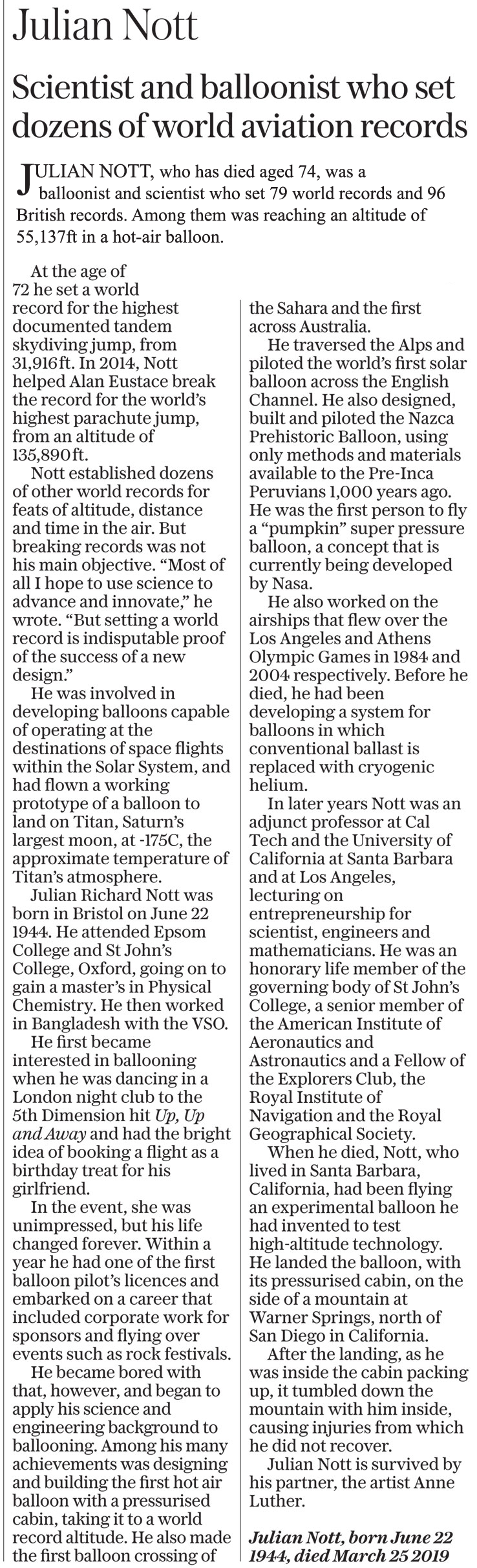

Julian Nott

Record-breaking high-altitude balloonist who was obsessed with safety but died after plummeting down the side of a mountain

April 30 2019, The London Times

Nott near Canterbury in 1981 TIMES NEWSPAPERS LTD

When Julian Nott undertook survival training with members of the US navy Seals, a special operations force, to prepare for the possibility of a balloon landing at sea, he was already 73 and the conditions were rough. He suffered hypothermia and was told to go to hospital. Instead, he went into Starbucks, drank coffee, had a doughnut and declared that he felt as well as he ever had done during a career setting 79 world records as a balloonist.

Nott had set a record for the highest documented tandem sky-diving jump — from 31,916ft — just the year before. “Sky-diving for me is like going to the dentist,” he said. “I do not enjoy it, but I know it’s good for me. And a good parachute, if you know how to use it, can save your life when all goes wrong flying experimental balloons.”

He designed and constructed one of the first hot-air balloons with a pressurized cabin, which he piloted to a record altitude of 55,134ft in one hour, nine minutes and 42 seconds. The cabin was the only item built after 1960 to be included in an exhibition staged by NASA, the American space agency, on high-altitude ballooning.

Nott’s other achievements included: the first crossing of the Sahara Desert and piloting the world’s first solar balloon across the Channel. He designed, built and piloted a prehistoric balloon, using only methods and materials available to the pre-Inca Peruvians, and built a Moët & Chandon champagne cork-shaped balloon that he flew over Mount Fuji.

Julian Nott, above, before the Channel crossing in 1981 TIMES NEWSPAPERS LTD

He also worked on a balloon designed to fly into space and piloted a prototype that was devised to land on Titan, the largest of Saturn’s moons, where the approximate temperature of the atmosphere is minus 175C. The balloon is still being developed, but Nott piloted it within an atmospheric simulator, which was filled with frozen nitrogen, at NASA.

Breaking records, however, was not his main goal. “Most of all I hope to use science to advance and innovate [ballooning],” he wrote. He was the first balloonist to be admitted to the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

Julian Richard Nott was born in Bristol in 1944, the son of Robert Nott, a company director, and his wife, Joyce, who had graduated from Girton College, Cambridge, and ran The Times Book Club. His parents encouraged him to explore his interest in science at a young age, setting up a laboratory in their garage, which he twice set alight. He took apart everything he owned, including toasters and computers, then put them back together.

After his parents moved from Bristol, he was educated at Epsom College in Surrey, and then St John’s College, Oxford, where he was captain of the college boat club. He took a degree in chemistry and later worked for Voluntary Service Overseas in Bangladesh. His first interest in ballooning was not exactly cerebral: he was dancing in a London nightclub to the song Up, Up and Away by the 5th Dimension when he decided to book a flight as a birthday present for his girlfriend. Ever the romantic, he would later give his long-term partner, Anne Luther, an artist, pink roses every week.

As his achievements grew, so did the nature of his sponsors, not least Moët & Chandon and Rolex. He was in demand as a public speaker and became a consultant for Google, NASA and others. According to Anne: “He was not completely fearless or brave in the traditional sense. He was thoughtful about every flight or item he designed, always looking at ways to make it safer. Once he gave it his final approval he relaxed in the knowledge that he had done all that he could and then ventured into some of the most dangerous situations.”

The couple met in 1989 over a business breakfast in New York, where he had been sent for three months by Airship Industries, of which he was a partner. Nott’s mission was to oversee the company’s recently acquired contract for a US Navy airship from an office in the Explorers Club. He became a US citizen in 2012, living in Santa Barbara, California. Nott also worked on the design of the airships that flew over Los Angeles and Athens for the Olympic Games of 1984 and 2004 and with surveillance balloons which flew over the recent Rio Games.

His approach to business was marked by a careful attitude to budgets. Even though he was 6ft 2in, he would curl up into a central economy seat on long-haul flights to save money for a sponsor or client.

Displayed prominently in his office were two quotes: “Do I dare disturb the universe?” and “Even the journey to the stars begins with a single step.” A psychic once told him that if he wanted to be recognized, he should put his name up in lights. Such advice resonated with him and he ordered a small custom neon sign of his signature, which he kept lit in his office. He trademarked the phrase “Math lets dreams take flight”.

Anne Luther reckoned that he was “a bit like a teenager when it came to authority”. She added: “He could be quite irreverent. Never in regard to flying or safety, but if there was a sign that said, ‘Do not enter’, he was through the door. ‘Do not touch’ was an invitation for him to embrace or examine something more closely.”

On one occasion Nott jumped over the red ropes at the Smithsonian, the world’s largest museum and research complex, so he could touch the Apollo space capsule. If a sign proclaimed, “No standing on the grass”, he would promptly do so, but with an impish grin. “Of course, he had his hand slapped by the authorities when caught, but he would usually charm them into forgiveness,” Anne said. “We had the most wonderful behind-the-scenes adventures.”

He was an avid reader of poetry and a passionate hiker, not least hiking up and down the Grand Canyon in one day in 2010. He hiked the hills around Santa Barbara County every week and completed 80 hikes last year. Although he was an early electronic adopter and always had the latest newest version, he wrote with a fountain pen.

Nott died when a balloon he had invented to test high-altitude technology landed on the side of a mountain at Warner Springs, California. Following the successful landing he returned to the cabin when it plunged down the face. His co-pilot suffered injuries, but survived.

Nott’s death shocked those who knew him because they were aware of his concerns about his safety.

“When we were first dating, we went to a country fair and I suggested we ride the Ferris wheel,” Anne said. “He refused, and I laughed and said, ‘You’re not afraid of heights, are you?’ He said that he wasn’t, but he didn’t know who had designed this wheel or assembled it and he wouldn’t take a risk riding it.

“When we were in Hawaii and I wanted to fly in a helicopter over the volcanoes, he spent three days interrogating operators on their ability to fly and their safety record before he selected one. This is why he had never even broken a bone flying or hiking. He was thoughtful and cautious, not fearless.”

Julian Nott, balloonist and scientist, was born on June 22, 1944. He died after sustaining injuries in an accident on March 25, 2019, aged 74